Genesis

of new aircraft types

"Everything

there ever was, was once just a dream"

Part

I - Velocity

Part

II Atlantica

Taking a

new concept to reality requires vision, know how, money and hard work. If

we never acted on our dreams human kind would not even have fire and the

club. Fortunately we do act and our standard of living gets better as a

result. Development of new aircraft is part of this process.

Velocity Genesis

Velocity Genesis

The

Velocity was conceived and acted on by Dan Maher in Dec of 84' as an

improvement to the popular Rutan design, the EZ. He had seen the molds and

assembly I was finishing up on another prototype called the "Sea

Shark". Dan liked my craftsmanship and invited me to work for him on

his new project so I started in the first of Jan 1985. He had begun the

fuselage and showed me the planform - it was sketched on a

napkin

As

we constructed components, detailed design decisions were made as we went.

Soon word leaked out that we were building a 4-place EZ type that aroused

many naysayers as well as constructive help. Ted Yon, EAA since 1954,

senior aerospace engineer, played the most important role advising on

rigging and structures. Ted, who is now also a FAA designated engineer,

did the span loading and resulting spar cap lay-up calculations as well as

our Wiffle Tree design.

The

scratch-built prototype flew in August of the same year. This pretty

little #1 Velocity exceeded all our expectations. The aerodynamic

engineering had been very basic but experience, intuition, luck and

stubbornness paid off.

I then

built the kit molds and started up production. While away from the

factory, I built my own personal Velocity that served faithfully for

years. With my own aircraft and bush pilot past I was able to push the

low-speed end of the envelope marveling at the Velocity's stable,

stall-proof characteristics. The Velocity was the first modern kit that

had utility, style, speed but most important of all it was relatively easy

to build. The reason for this was that Dan and I used our prior boat

building experience to modularize the components. This integration of many

parts into just a few big ones produced the industries first true

"fast built" kit.

This was

done by design such that less assembly was required as the parts came from

the mold not because of factory post molding sub-assemblies. As the

Velocity became more popular the need for a better method of wing

fabrication became obvious so I formed Dynamic Wing Company and started

the evolution of my new solid core pressure molding.

Like the

Velocity itself, the closed molding system my team and I perfected worked

better than anticipated. We have since delivered over 180 complete sets of

wings to very happy customers.

Part II

ATLANTICA

This is the

culmination of over 30 years of aerodynamic and composite study and

experimentation on my part. My curiosity in these areas started at a young

age. In 1962 when I was 12, I built a gas powered flying wing of my own

design that provided many hours of fun. That same summer I built my first

surfboard that was also a lot of fun until a big wave broke it in half.

This was just the beginning of my lessons in structural engineering. At 8

years of age I won the first sail boat race I entered. At 16 I won the

first surfing contest I entered and at 18 I supervised the hull design and

lay-up, helping my older brother win the Bahamas 500 off-shore powerboat

race. In the late 60's I started using epoxies and multiple fins on my

surfboard designs. I had a garage at the time and went through a period of

rapid development in board shaping. I have since seen many of my ideas

become the standard. While in ocean engineering school, I developed my own

hydrofoil design that was later adapted to carbon fiber wind surfers I had

made. This challenging development in fluid dynamics and structures I've

always done as a competitive hobby with no commercial intent.

My full-scale aircraft

experience didn't come about until I was in my twenties. I had a P-18 and

later bought the first 540 Lycoming Powered Maule and flew it down to

Costa Rica to run our ranch. I used that plane as a real workhorse and

gained an understanding of low speed flight and stall characteristics.

When I returned in '79 I went to Oshkosh, camped out of my Maule, and had

my eyes opened up to an entire world of possibilities where I could use my

design and composite skills to do something that I love.

The Atlantica is a

relatively recent development for me with it's roots starting at Sun N'

Fun '97. I had my pressure molded wings on display with some models of my

slide-rule designed aircraft in front. A fellow stopped by to talk design.

He turned out to be a top-level military aerodynamic engineer from Wright

Pat. He was unable to give up "secrets" but showed interest in

my highly integrated wing molding process. Later on, he dropped by a

second time and pointed out that my process lent itself to easy

construction of some emerging designs.

In 1998, I met Austin

Meyer, a young aeronautical and computer whiz who had developed an

intriguing software package using Open GL in order to provide extremely

realistic simulations. The

program, X-plane

is based on blade element

analysis and calculates moments to a high resolution in real time (at

least 15 times per second). The graphics interface of X-Plane makes it

appear to most people as a simple flight simulator game but it is based on

real engineering and I immediately saw its potential as a concept design

tool.

Over the next year I

designed hundreds of airplanes with this tool, and worked closely with

Austin verifying the program's accuracy. This was FAR more advanced

than the napkin sketch that started the Velocity (see part I)

What

evolved resembled a bird by the time performance and handling had been

optimized. This fairly conventional design had great numbers and style,

but as I studied closely how to produce my "x-bird" its

complexity of manufacture and high parts count became glaringly evident.

In Dec '98 I remembered that nice man from Wright Patterson and the BWB

that had "pitch

generating capability". I knew it would be easy to build, especially

with my proprietary Pressure Molding Process, but how would I make it fly

right? This sent me off researching for what BWB's really looked like.

What

evolved resembled a bird by the time performance and handling had been

optimized. This fairly conventional design had great numbers and style,

but as I studied closely how to produce my "x-bird" its

complexity of manufacture and high parts count became glaringly evident.

In Dec '98 I remembered that nice man from Wright Patterson and the BWB

that had "pitch

generating capability". I knew it would be easy to build, especially

with my proprietary Pressure Molding Process, but how would I make it fly

right? This sent me off researching for what BWB's really looked like.

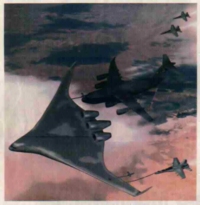

By 1944 the Horten brothers' flying wing HO-9 had advanced into a partial

BWB with some very important rigging and control features. Critical

details that are essential to stability.

The next place I went

was NASA, which led me to Dr. Ilan Kroo's work at Stanford University.

Then I took a closer look at the many renditions of future military

designs discussed in "Aviation Week" and other resources.

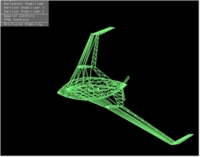

With a refreshed

understanding of the BWB as compared with Flying Wing designs, I returned

to a component of X-Plane, called "Plane-Maker . This

allows the user to create an aerodynamic model of anything imaginable

(pretty much) and fly it in the real-time simulation of X-Plane. The

results of entering a BWB configuration were immediate and dramatic.

By the time Sun N'Fun came

around, I had several models of personal BWB's that out-flew any of my

previous designs.

Then with my notebook PC

and X-Plane, I was able to show these designs - in flight - to many old

friends. It was very exciting but their reactions were skeptical. I found

myself reminding them that the math hadn't changed. "X-Plane replaces

all of the pencil pushing that 'slide-rule' designers labored over for

months in order to understand a new shape, only in real-time."

At this point I had over

a year's experience with the program and a good rapport with it's author

developed over long conversations regarding the accuracy of the program.

The "control" aircraft that came with the program, like the 172,

Baron etc. all fly correctly as personal experience has shown me. The

program and blade element analysis provide very realistic output,

including failure modes, and gusty weather situations. Likewise, my own

designs always reacted to changes in a logical manner.

It is more accurate than

scale models, and has advanced the design process beyond any point that I

expected to experience or had available when I helped build the first

Velocity.

Later

in '99 I started using Dr.

Hanley's "Visual Foil" software to find the correct airfoils

to further optimize my Personal BWB designs. First I analyzed the Reynolds

numbers for sections across the span. Then I used this information in

conjunction with my specific rigging requirements to search for the proper

airfoils for each station on the Z-axis. In the software's library of over

one thousand airfoils I was not able to find any that provided docile

characteristics, laminar flow and allowance for efficient rigging at the

same time. As a result I had to design my own new family of airfoils to do

the trick.

Later

in '99 I started using Dr.

Hanley's "Visual Foil" software to find the correct airfoils

to further optimize my Personal BWB designs. First I analyzed the Reynolds

numbers for sections across the span. Then I used this information in

conjunction with my specific rigging requirements to search for the proper

airfoils for each station on the Z-axis. In the software's library of over

one thousand airfoils I was not able to find any that provided docile

characteristics, laminar flow and allowance for efficient rigging at the

same time. As a result I had to design my own new family of airfoils to do

the trick.

Fortunately,

computer wind tunnels are more accurate and less likely to lead a designer

astray because testing is always done with full-scale Reynolds numbers.

This is important because most wind tunnels are operating with air that is

at sea level pressure density. Air molecules affect aerodynamics in

proportion to the size of the body being acted on as well, so a small

model in a real wind tunnel is effectively flying in pea soup, hardly as

accurate as we like. (Here is a strange case of the virtual model being

closer to reality than a physical model)

Fortunately,

computer wind tunnels are more accurate and less likely to lead a designer

astray because testing is always done with full-scale Reynolds numbers.

This is important because most wind tunnels are operating with air that is

at sea level pressure density. Air molecules affect aerodynamics in

proportion to the size of the body being acted on as well, so a small

model in a real wind tunnel is effectively flying in pea soup, hardly as

accurate as we like. (Here is a strange case of the virtual model being

closer to reality than a physical model)

Once the airfoils were

complete, I went back to my old fashioned drawing board with a pencil and

worked out the internal details. This includes ergonomics, mechanics and

structures. The BWB shape really lends itself to the plumbing and hardware

space requirements of an aircraft. The cabin is free of a center tunnel,

and still has 10cu ft. of cargo with room for skis or a long surfboard.

Finally I was able to

plot some full sized templates for the mold masters. The

technique I use to make these forms is just a jumbo version of what a

professional surfboard shaper taught me in 1966. I take foam blocks, cut

them, and shape bevels before rounding. The

system is very accurate and fast for someone like myself who has shaped

hundreds of surfboards.

It helps also in this

case that the designer, draftsman and toolmaker are all in the same head

... mine